Formula 1 Fatalities: A Detailed Analysis of Each Tragedy, Trends & Safety Evolution

Table of Contents

Why F1 Fatalities Still Matter in 2025

In the shadow of Formula 1’s gleaming innovation and global fanfare lies a sobering truth: the sport’s DNA was written in danger. For all the technical brilliance and driver heroics we celebrate, it was tragedy that most often drove real change.

Two names still echo loudly when this subject arises: Jules Bianchi and Ayrton Senna. Bianchi’s 2014 crash at Suzuka remains the last fatality in a World Championship event, a haunting reminder that even in the age of data, carbon fiber, and simulations, unpredictability still lingers. Senna’s death 20 years earlier, during the infamous 1994 San Marino Grand Prix weekend, didn’t just end a career—it rewrote the sport’s approach to safety forever.

This article explores the history, statistics, and significance of Formula 1 fatalities. It breaks down the numbers by decade and nationality, revisits landmark crashes, and outlines how tragedy ultimately became the catalyst for today’s safety-first approach. From testing sessions to non-championship events, each death left its mark on the sport’s evolution.

But this isn’t just a timeline—it’s a reflection. Through the lens of loss, we better understand the resilience of motorsport, the legacy of drivers who paid the ultimate price, and the safeguards protecting the champions of tomorrow.

Understanding Formula 1 Fatal Accidents

Definition & Scope

In the context of this article, a Formula 1 fatality refers to any driver death directly resulting from an incident in:

- World Championship races

- Practice or qualifying sessions

- Private or official testing

- Non-championship Formula 1 events

- Demonstration runs or historic F1 races (post-career)

This broader scope provides a clearer view of the sport’s risk landscape. For example, drivers like Jules Bianchi (2014) and Elmo Glick (1950) died in vastly different eras and circumstances—but both incidents are integral to understanding F1’s relationship with danger.

Some fatalities occurred in off-season or demonstration runs, like Carel Godin de Beaufort’s 1964 crash during practice for the German Grand Prix or Cameron Earl’s 1952 test crash in a BRM. These non-race events, while often overlooked, proved just as lethal.

Understanding this variety helps us trace patterns and identify key failings—be they mechanical, organizational, or environmental—that cost lives and eventually shaped regulations.

Key Statistics at a Glance

Formula 1’s fatal history is best understood when broken down by era, nationality, and type of session. The following tables summarize the available data up to 2025.

Driver Fatalities in F1 by Decade (Championship + Non-Championship)

Numbers alone don’t convey the emotional weight of F1’s dangerous past—but visualizing the data brings sobering clarity. Below are conceptual visual elements that, if presented interactively, could offer deeper insight into the patterns and evolution of Formula 1 fatalities.

| Decade | Number of Fatalities |

|---|---|

| 1950s | 15 |

| 1960s | 14 |

| 1970s | 12 |

| 1980s | 7 |

| 1990s | 4 |

| 2000s | 0 |

| 2010s | 1 (Bianchi, 2014) |

| 2020s | 0 (as of 2025) |

This visualization underscores how the sport’s danger was concentrated in its early decades, followed by a steep decline after the 1994 Imola weekend. The 2000s mark the beginning of a new era in safety.

Fatalities by Session Type

| Session Type | Number of Deaths |

|---|---|

| Grand Prix Races | 22 |

| Practice/Qualifying | 14 |

| Testing | 6 |

| Non-Championship Races | 12 |

| Demo/Historic Events | 2+ |

Most Affected Circuits (F1 Fatalities)

A heat map of the most lethal circuits would show red markers over:

| Circuit | Fatalities |

|---|---|

| Nürburgring (Germany) | 5 |

| Monza (Italy) | 5 |

| Spa-Francorchamps (Belgium) | 3 |

| Zandvoort (Netherlands) | 2 |

| Silverstone (UK) | 1 |

| Suzuka (Japan) | 1 (Bianchi) |

These circuits were often high-speed with minimal safety features in earlier eras. Modern upgrades—including extensive run-off zones and better marshal response systems—have significantly improved their safety records.

Fatal vs Survived High-Impact Crashes

| Crash | Speed | Outcome | Safety Element That Helped |

|---|---|---|---|

| Senna, Imola (1994) | ~230 km/h | Fatal | Lacked head protection |

| Bianchi, Suzuka (2014) | ~212 km/h | Fatal | No Halo, recovery vehicle exposure |

| Grosjean, Bahrain (2020) | ~190 km/h | Survived | Halo + fire suit + survival cell |

| Zhou Guanyu, Silverstone (2022) | ~270 km/h | Survived | Halo + roll hoop (partial failure) |

This contrast shows how modern safety devices have shifted outcomes. Crashes that would have likely been fatal in the 1970s or 1980s are now survivable, even at higher speeds.

Driver Fatalities by Nationality (Top 5)

| Nationality | Fatalities |

|---|---|

| British | 9 |

| Italian | 7 |

| French | 6 |

| American | 5 |

| German | 4 |

📝 Note: These figures combine both official F1 events and relevant non-championship accidents and are based on compiled FIA, Wikipedia, and historical archives. Some non-official reports may vary by source.

These numbers paint a chilling picture: while the danger has decreased dramatically since the 1990s, each decade until the 2000s experienced regular loss. The complete halt in fatal F1 crashes since Bianchi is a testament to modern safety—yet it’s not a guarantee for the future.

Next, we explore the timeline of major crashes that shaped these numbers—and the sport itself.

Timeline of Tragic Crashes

1950s–1960s – The Deadly Dawn

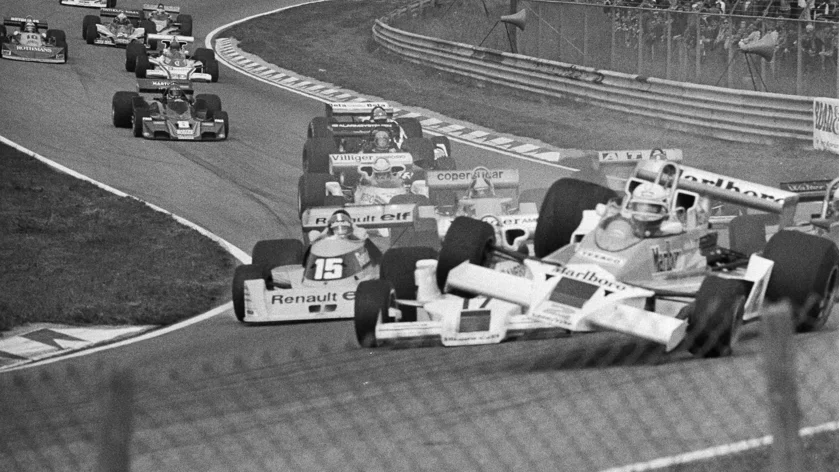

The earliest decades of Formula 1 were, in many ways, an age of experimentation—fast cars, open cockpits, and few rules. Unfortunately, that combination also made the sport terrifyingly dangerous.

Drivers wore little more than leather helmets and cotton overalls. Tracks like Monza, Spa, and Nürburgring featured high-speed straights lined with trees, walls, or ditches—and almost no run-off zones.

One of the first significant losses came in 1952, when British engineer Cameron Earl died while testing a BRM V16. Though not in a race, the crash highlighted the lethal risks of early F1 car development.

Among the most devastating moments of the 1960s was the 1961 Italian Grand Prix. German driver Wolfgang von Trips collided with Jim Clark’s Lotus, sending his Ferrari airborne into the crowd. Von Trips and 15 spectators were killed. It remains one of the deadliest days in F1 history—not just for its toll, but for the sheer horror of its setting: the home of speed, Monza.

Other fatal names from this era include:

- Onofre Marimón (1954) – first F1 fatality during a Grand Prix weekend.

- Stuart Lewis-Evans (1958) – engine fire during the Moroccan GP.

- Chris Bristow and Alan Stacey (1960) – both killed within minutes at Spa.

By the end of the 1960s, the death toll was mounting too fast to ignore. But change was still slow, and the 1970s were waiting with more heartbreak.

1970s–1980s – Turning Point for Safety

The 1970s arrived with the roar of powerful engines—and a sense of dread. Drivers like Jochen Rindt, who became the sport’s only posthumous World Champion, lost their lives before they could see the title confirmed. Rindt’s death at Monza in 1970, due to brake shaft failure and lack of seatbelt use (ironically, his choice), stunned the paddock.

The era’s brutal reality was best summarized by Niki Lauda, who survived a near-fatal inferno at the Nürburgring in 1976:

“From one race to the next, I wasn’t sure who’d be missing in the drivers’ briefing.”

Some of the more tragic losses during this time included:

- Roger Williamson (1973) – trapped in an overturned car at Zandvoort, left to burn with little trackside assistance.

- Tom Pryce (1977) – struck a marshal running across the track at Kyalami.

- Patrick Depailler (1980) – lost control in testing at Hockenheim.

By the 1980s, incremental safety changes were in place: improved helmets, fireproof suits, and better marshaling. Still, the death of Elio de Angelis in 1986 during a test session again revealed how gaps in safety persisted—there were no fire marshals near the crash site.

Safety was evolving, but the most definitive shift came in the next decade—triggered by one of the darkest weekends in motorsport history.

1990s–2000s – The Dark Weekend at Imola

The 1994 San Marino Grand Prix is seared into Formula 1’s memory. The weekend was supposed to be just another chapter in a championship battle—but it unraveled into a nightmare.

On Friday, Rubens Barrichello suffered a horrifying airborne crash. He survived, but it was a sign of things to come.

On Saturday, Austrian driver Roland Ratzenberger died during qualifying after a front wing failure sent his car headlong into a concrete wall at over 300 km/h.

Then, on Sunday, came the unthinkable: Ayrton Senna, three-time World Champion and beloved by millions, crashed at Tamburello on Lap 7. A piece of suspension pierced his helmet. He was airlifted to hospital but died later that day.

That weekend forced an immediate reckoning. The FIA introduced sweeping changes:

- Speed-reducing chicanes at high-risk corners.

- Stricter crash structure regulations.

- Head and neck protection systems (HANS).

- Revamped pit lane speed limits and cockpit dimensions.

The result? Between 2001 and 2013, no F1 driver died in a championship session.

The 2000s, in contrast, were a calm period in terms of fatalities. While crashes still happened, no driver lost their life on track—thanks to lessons learned the hard way at Imola.

2010s–Today – After Bianchi, No Wheel Fatalities

The sport’s modern era has become a testament to engineering progress—but not without sacrifice.

In 2014, at the rain-soaked Japanese Grand Prix, French driver Jules Bianchi aquaplaned off track and struck a recovery vehicle that was attending to another incident. The collision was catastrophic. He sustained severe head injuries and died in July 2015, after months in a coma.

Bianchi’s death was the turning point for the halo device, a titanium protective ring around the cockpit introduced in 2018. Initially controversial for its aesthetics, the halo soon proved its worth, notably in saving Romain Grosjean during his fiery 2020 Bahrain GP crash.

Since Bianchi’s passing, no driver has died during an F1 event. The streak is the longest in modern F1 history.

While fatalities have occurred in lower formulas and historic car events, Formula 1’s top tier remains — for now — safer than it has ever been.

In-depth Case Studies

The broader history of Formula 1 fatalities is shaped by individual stories—each unique, each devastating, and each instrumental in transforming how the sport views risk. Some crashes echoed beyond the paddock, triggering safety revolutions and leaving legacies that persist today.

Ayrton Senna (1994) – The Basis for Modern Safety

Senna’s crash at Tamburello corner, Imola, wasn’t just the death of a sporting icon—it marked a cultural and procedural shift within Formula 1. At the time of his accident, Senna was already campaigning for greater safety, having expressed concerns following Ratzenberger’s death the day before.

Cause: A suspected steering column failure, combined with low tyre pressure due to the safety car start, caused his Williams FW16 to veer straight into a concrete wall at over 230 km/h.

Aftermath:

- FIA president Max Mosley launched the Advisory Expert Group on safety.

- New crash test standards were introduced.

- Circuits were redesigned to include wider run-off areas.

- Development began on devices that would later evolve into the HANS system and Halo.

Senna’s death wasn’t in vain—it jumpstarted the modern safety movement, and his legacy is deeply entwined with every precaution seen on the grid today.

Jochen Rindt (1970) – The Only Posthumous World Champion

Jochen Rindt’s death at Monza was a stark reminder that championship glory is fragile in F1. His Lotus suffered a brake shaft failure during practice, sending the car into barriers that lacked adequate energy absorption.

Despite missing the final races, Rindt had already accumulated enough points to win the 1970 title posthumously—an unmatched, eerie footnote in F1 history.

His crash became a case study in component failure, prompting deeper scrutiny of mechanical tolerances and driver protection during high-speed testing sessions.

Jules Bianchi (2014) – Halo’s Precursor

Jules Bianchi’s accident was as preventable as it was tragic. In the closing stages of the 2014 Japanese Grand Prix, yellow flags were deployed for Adrian Sutil’s crash. A tractor crane was dispatched to remove Sutil’s car. Moments later, Bianchi lost control and slid off at nearly the same point—slamming directly into the vehicle.

Injuries: Severe diffuse axonal brain injury.

Legacy:

- Sparked outrage over race control decisions in poor weather.

- Led to the Virtual Safety Car (VSC) system.

- Became the emotional anchor for the Halo debate—his family supported its mandate.

Today, the Halo stands as a silent tribute to Bianchi. His accident changed minds, laws, and lives.

Wolfgang von Trips (1961) – The Spectator Tragedy

The 1961 Italian Grand Prix was poised to be von Trips’ crowning moment. But a high-speed collision with Jim Clark’s Lotus resulted in von Trips’ Ferrari flipping into the crowd at Parabolica. He was killed instantly—along with 15 spectators.

It remains one of the most devastating events in motorsport not only because of the driver fatality, but because it exposed track design shortcomings that endangered fans.

Monza’s layout was altered in the years that followed, with changes to fencing, spectator placement, and corner profiles. The crash helped ignite global conversations about circuit safety—not just driver safety.

Safety Evolution & FIA Regulations

Safety Measures Born from Tragedy

Many of Formula 1’s most important safety innovations were born in the wake of devastating loss. The sport evolved reactively—each major tragedy prompted a technical or procedural leap forward.

Key advancements over the decades include:

- Full-face helmets (standardized in the 1970s)

- Fire-retardant suits and gloves

- Survival cells (introduced in the 1980s, made from carbon fiber monocoques)

- Wheel tethers to prevent tyres detaching and striking others

- Pit lane speed limits introduced after mechanics were killed in service zones

Even track designs shifted—from open public roads to purpose-built, barrier-lined circuits with gravel traps and large run-off areas.

These weren’t luxuries—they were hard-earned necessities, shaped by the lives that had been lost.

Halo & Modern Safety Tech

The Halo, implemented in 2018, remains the most visually obvious—and perhaps most controversial—safety feature in F1. Designed to deflect debris and protect drivers from cockpit intrusion, it’s already proven its worth multiple times.

Notable incidents:

- Romain Grosjean (2020, Bahrain GP): Survived a 137 mph crash and fireball.

- Lewis Hamilton (2021, Monza): Halo deflected Max Verstappen’s wheel from striking his head.

In addition to the Halo, modern safety standards now include:

- Biometric gloves for real-time health monitoring

- Survival cell deformation zones

- Mandatory crash tests for chassis and suspension systems

The FIA continues to invest heavily in predictive modeling, AI crash simulations, and even augmented reality overlays for marshal positioning.

Insights from Safety Studies

A 2024 study published in the arXiv preprint server titled “Statistical Analysis of the Impact of FIA Regulations on Safety, Racing Dynamics, and Spectacle in Formula 1” found that:

- The frequency of fatal incidents per race dropped by 98% between 1960 and 2020.

- The probability of surviving a 200+ km/h crash increased from ~60% in 1980 to over 99.8% by 2023.

- Key turning points in risk reduction aligned closely with the Senna reforms (1994) and Halo implementation (2018).

This data highlights how F1 has successfully balanced entertainment and danger—without compromising its soul.

Lessons & The Road Ahead

Formula 1’s history of fatalities is not just a cautionary tale—it’s a chronicle of transformation. Each name lost along the way reshaped a part of the sport, and every regulation today stands on the shoulders of that sacrifice.

What’s Improved:

- Car design now prioritizes the survival cell as a fundamental structure.

- Circuits feature vast run-off areas, TecPro barriers, and real-time marshal oversight.

- Onboard safety includes biometric sensors, Halo devices, and HANS systems.

What Still Needs Vigilance:

- Urban street circuits with limited run-off remain a concern.

- Extreme weather—as seen in Bianchi’s crash—poses ongoing risks.

- The rise of alternative fuels and electric components introduces new fire hazards.

Safety in F1 has reached unprecedented heights, but it’s not a static achievement. It’s a living system—updated every time the lights go out on race day.

The goal is no longer just about surviving F1—it’s about ensuring that no one else has to die for it to evolve.

Conclusion

Formula 1 has always balanced on a razor’s edge between glory and danger. Its allure stems from pushing limits—but history has shown that pushing too far, without protection, exacts a devastating cost.

Today’s safety innovations—Halo, virtual safety cars, fire-resistant gear—exist because others didn’t survive. Remembering those drivers isn’t just respectful; it’s essential. They were the price paid for the sport we now admire.

As F1 speeds into the future—with smarter cars, more daring venues, and evolving technologies—its commitment to safety must remain uncompromising. Because every life saved isn’t just a triumph of engineering—it’s a victory of memory, responsibility, and progress.

FAQs

How many drivers have died in Formula 1?

As of 2025, over 50 drivers have died due to accidents in Formula 1-related sessions, including championship races, testing, and non-championship events.

When was the last Formula 1 fatality?

Jules Bianchi in 2014, following a crash at the Japanese Grand Prix. He passed away in July 2015 due to head injuries.

Why did Jules Bianchi crash?

Bianchi lost control in wet conditions under yellow flags and collided with a recovery vehicle. The absence of safety car deployment and poor visibility were key factors.

What is the Halo in F1?

The Halo is a titanium protective bar mounted above the cockpit to deflect debris and protect the driver’s head. It was mandated in 2018 after extensive testing.

Which F1 weekend had multiple fatalities?

The 1994 San Marino Grand Prix weekend at Imola—Roland Ratzenberger died during qualifying, and Ayrton Senna during the race.